Looking Good — Desktop Environments, Window Managers and Compositors

But can it look nice?

Hey! You! Yes, you. Turns out I'm back with another post. Are you running Linux yet? No? Maybe you need more info before you switch? I can understand that.

Over the next few articles, we are going to cover many different use cases for Linux, like content creation, artists, gaming, and so on. After that, we'll get right into the minutiae of Linux. You'll get to know the terminal, how different systems work, and how to customize them.

Now? We're talking about looks. You would like your system to look nice, right?

So, if you're interested in my upcoming write-ups and want to get more and more familiarized with a possible new way of using your computer, make sure to subscribe!

Well, with that bit of housekeeping out of the way, I can talk to you about desktop environments. We'll have a history lesson too.

In a cave, made of scraps

Over 30 years ago, a guy from Helsinki decided to write a hobby project. You know, just a fucking kernel. His name was Linus Torvalds, and it became kind of a big deal. I'll write about the history of Linux in a future extra article, but for now, let's focus on a simple fact: A kernel is not a complete operating system.

It's a very important part, arguably the most important part, but it's not the whole thing. There's nothing drawing stuff to the screen; all you've got is text. There are no programs, there's nothing designed for it. It's just an engine without any machinery taking advantage of it.

Linux wasn't just a completely new ordeal. Torvalds made a big effort to design it in accordance with the POSIX standard. Believe me, I'll tell you about it some other day. Let's just say that a bunch of software, even free and important software, had been made years before Linux and was immediately compatible with it.

How is that possible? Well, imagine the physical ports on your PC. They're designed to pass information in and out of your computer to whatever you connect to them. As long as both your computer and whatever gear you connect correctly use the standard for a given port, it should always work.

Ideally, the system in your computer and the gear you are connecting could either be or both be completely new technologies that the guy who designed the port couldn't have even dreamed of, but if they apply the standard correctly, they should talk.

Your e-mail is another great example. The vast majority of e-mail follows the same standard. You could be using a cyberpunk abomination of a server to receive the mail while other people use Gmail, or vice versa. But as long as both of you have implemented e-mail correctly, the thing will work.

The same is true for Linux. It's a new kernel, but it's still interoperable with many different technologies. One of them was called X. Or X Window System. Or X11. This software has been on version 11 since 1987. And it's still in use today, although there are very strong efforts to modernize the stack.

I won't bore you with a complete story now, so be assured: this is a venerable graphics stack that has allowed multiple systems, including Linux, to show windows, UIs, and graphical interfaces since the very beginning.

Its importance can't be understated, and it's still a very popular option, although it's mostly feature frozen, and most work has moved towards improving its successor, Wayland.

The point is, Linux was a new project, and it quickly gained some very important features thanks to that interoperability. Linus didn't have Microsoft's budget, but it didn't matter: Linux quickly became a community effort, and the collective work of thousands of people was being applied to build something new.

Yes. I will talk about GNU in the Linux history article, don't worry.

(If you don't know what I'm talking about, don't worry, just ignore it.)

X11 proved to be a very useful way of creating interfaces. As a windowing system, it enabled a lot of different ways of interacting with your computer. These systems all have their own interfaces, philosophies, and ways of controlling the screen.

We commonly refer to them as desktop environments. It's basically the GUI of your computer. The way it looks, but also the programs it comes with.

Traditionally, Linux users use the terminal for everything. So, if you want to give users an image viewer, an interface for searching through files, a way of setting configuration options without editing text files, well... you need to program all that.

And many people did. We had some wonderful variety from that effort.

Some people decided to make lighter implementations. Instead of emulating Windows, the focus was kept on the keyboard. The windows didn't float; they just occupied a set space and adjusted when you opened something new. It was quick and intuitive once you learned the ropes.

These environments were called window managers, and the most common were the tiling variety, where windows occupy the screen and start resizing as you open new things, instead of just floating one on top of another.

It's my preferred method of computing, but I'll tell you all about it later.

The main difference between a desktop environment and a window manager is that a WM is just a way of controlling the windows and interacting with the system. Everything else you need to make yourself or install from a third party.

A desktop environment, however, is a more complete affair. It comes with a way of interaction, a graphical user interface, and usually many different programs one could need to use, from file managers to image viewers to text editors, and so on and so on.

Most of the things I'll be recommending today are full-fledged desktop environments. There will be some window managers (or rather, their successors) thrown into the mix in the later part of the article, though.

New lands, far away

The Wayland protocol was first launched in 2008, looking to modernize the Linux graphical stack. Arguably, it succeeded, although it took about... twelve years? A bit more?

Replacing X11 is kind of a big deal, as you can imagine. And the whole thing needed a lot of time before reaching a level of maturity and coordination acceptable for regular use.

Wayland used to be sneered at, and maybe a few years ago, there were still serious problems that needed to be ironed out. By now, however, it's pretty mature and stable, and most distros and desktop environments are switching or planning to make the switch.

Sadly, Wayland is not backwards compatible, so a X11 desktop will not work out of the box in the new system. Workarounds are being worked on, but I don't think it's useful for this article to focus too much on those.

Wayland's version of the window manager is called a compositor. Won't bore you with the technical details, but, technically, X11 was a compositor too; it's just that Wayland is lower level and distros and DEs get to choose or build their compositors too.

Okay! Let's talk about some interesting interfaces you might be curious about using.

A Rundown of Interfaces

GNOME

Lots of people have lots of things to say about GNOME. I won't bore you with it: it works. It's slick, functional, and has a great feel on laptops.

There are some problems, though. GNOME makes some particularly weird decisions, like not having a system tray. You can add an extension for that. But why?

I'd describe GNOME as a hyper-usable space with very minor customizability. You can try to visually customize it, but it'll probably break next update. It's best to use it as-is, save for the extensions you need to make your workflow function.

If you don't mind that, however, GNOME has a lot to like. Menus and interfaces are intuitive, you get fantastic gestures for touchpads, and the dynamic workspaces (you get new spaces to your right as you use the ones that are available, and empty workspaces get deleted) are incredibly useful.

I haven't used GNOME in a while, but I think it's a prime candidate for anyone looking to breathe life into their laptops. Most distributions offer it by default or as one of their options. So it's hard to go wrong with it... as long as you don't mind a rigid experience.

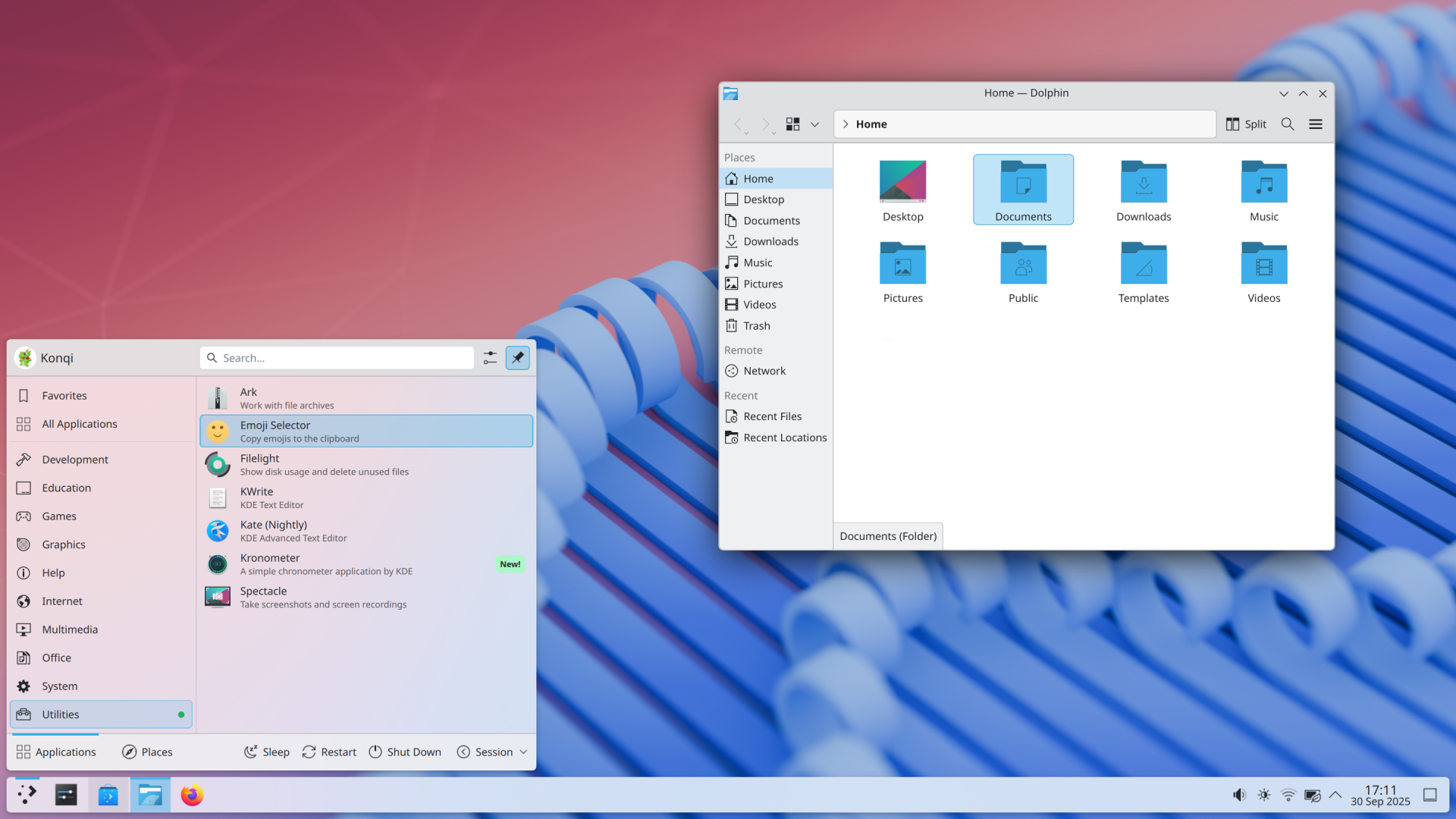

KDE

KDE is a very different beast. There are countless customization options, both for the appearance of the system and for its function. Despite this, the default workflow is very reminiscent of Windows in its layout, so it might be more intuitive to newcomers.

You can change panels, add widgets, move sections, you can do so much! Maybe too much? I'm not one to think so, but don't feel like you have to personalize everything all at once. Take your time.

KDE is incredibly versatile and very stable. It was my workhorse for a few months before taking the plunge and moving to a compositor/tiling window manager. It's a fantastic system that you should probably consider.

COSMIC

Well! Here's someone new. COSMIC is a weird beast. It also just launched its beta. This is very new software, made by the people at System76. It takes some design cues from GNOME, but it's clearly much more focused on customization.

You could consider it a middle ground between KDE and GNOME, and that's an apt way to put it. But it's also a middle ground with tiling window managers, since you can toggle your windows so they all conform to a grid, and you can move around with the keyboard.

It's a fantastic hybrid experience that might let you enjoy both the quickness of tiling window managers and the versatility of regular desktop environments. If you don't mind being early and finding a bug or two, you could give it a shot!

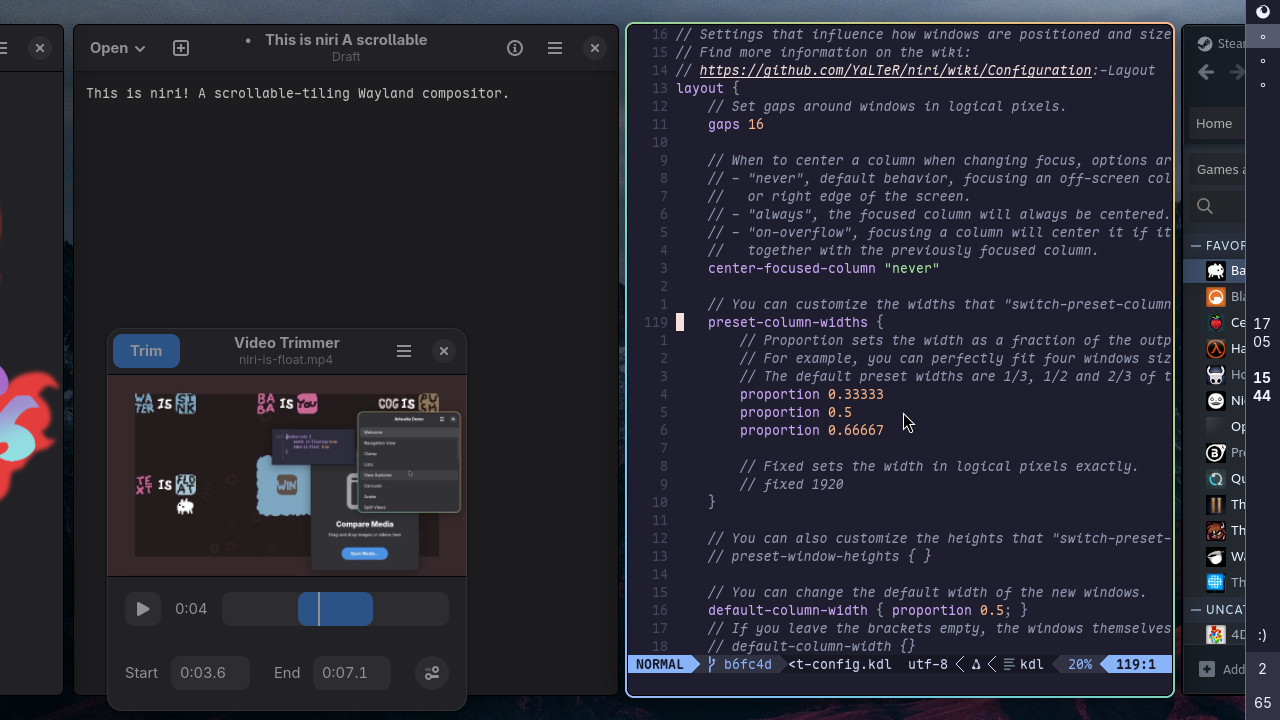

Hyprland

Hyprland is a tiling window manager for Wayland. You know how most OSs just have the windows floating around? Hyprland and other twms follow a different workflow: each window gets a position on screen, dividing it into different tiles. You can move the windows around and to different workspaces, but they never overlap.

Hyprland shines when you're using the keyboard to move around. It's trivial to create shortcuts for apps and move around your environment at blazing speeds. It's also very customizable, with support for animations, gradients, and a bunch of eye candy.

Hyprland is a tinkerer's paradise, but it might be a tough ask for newcomers. It's configured via text files and, as you've read already, it's not a desktop environment, so you have to pull programs and utilities from other projects. (That said, the dev has made a pretty awesome ecosystem out of utilities for Hyprland, check their wiki.)

This is the compositor I use. I won't recommend it if you're totally new to the business, though. It might be overwhelming. I'm planning on covering how to set up Hyprland in a future article, though!

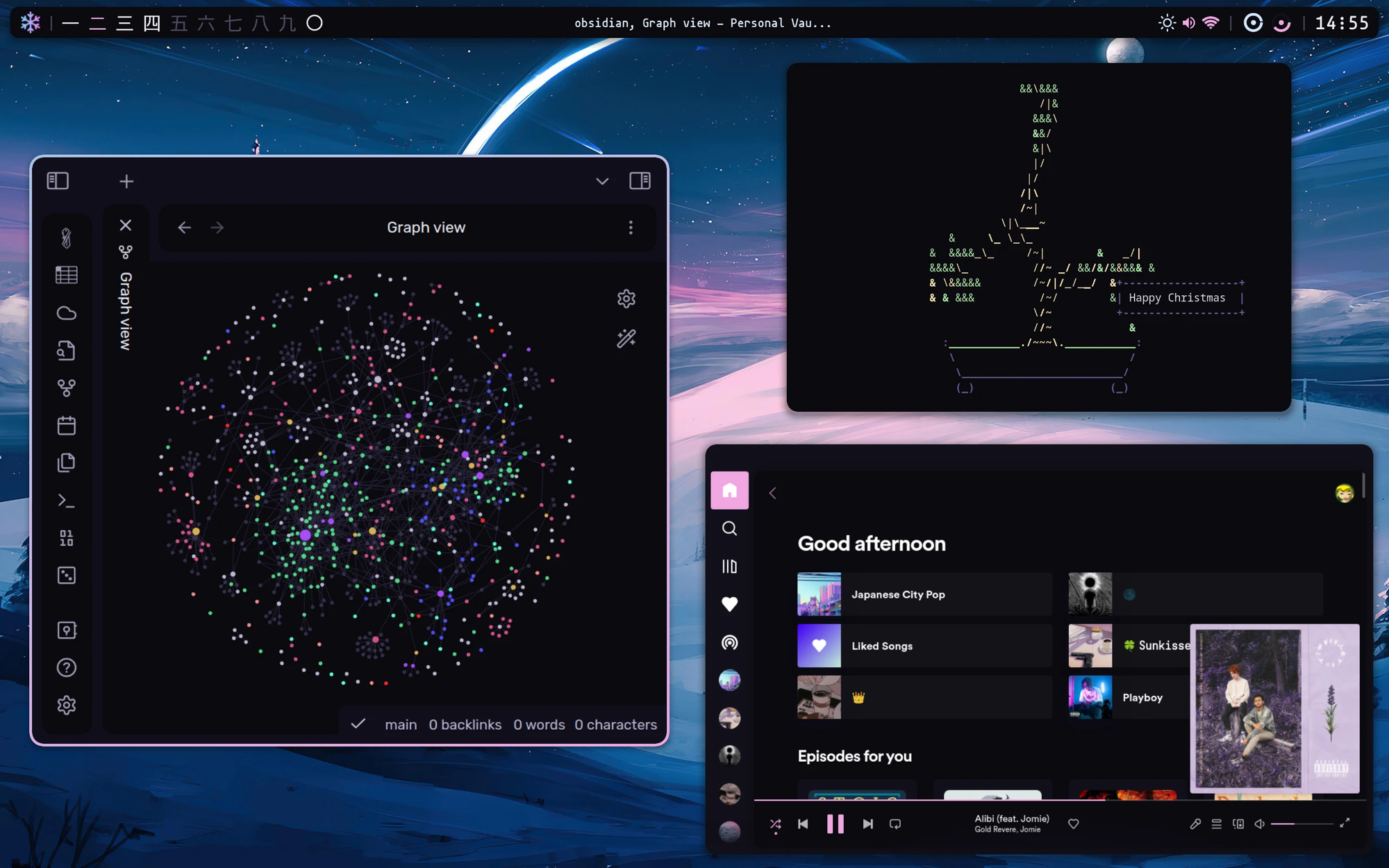

Niri

Niri is slick and fun. It's been called a scrolling window manager. You see, it tiles like Hyprland. But you have infinite horizontal space! Windows keep opening to the left, and you can scroll around or use the keyboard.

It's surprisingly versatile and great if you need to keep many things open on a single workspace. As Hyprland, it comes with the bare essentials, but you can quickly build up a pretty awesome shell (user interface) if you're inclined.

I plan on talking about configuring Niri, too! That's for another day, however.

That's all, folks!

I hope you've enjoyed this write-up. I plan on alternating between going in-depth and doing more lightweight articles, maybe that way I'll have a decent pace for once.

If you enjoy my writing or found it useful, consider buying me a coffee. It really means a lot!

See you next time.

Love, Clari. 💙